Лизавета Ивановна сидела...

Lizaveta Ivanovna was sitting...

We will continue with the full-sentence building exercises, borrowing from The Queen of Spades by A. S. Pushkin. Please have a look at the previous takes here and here if you like this kind of approach. And now to today’s sentence.

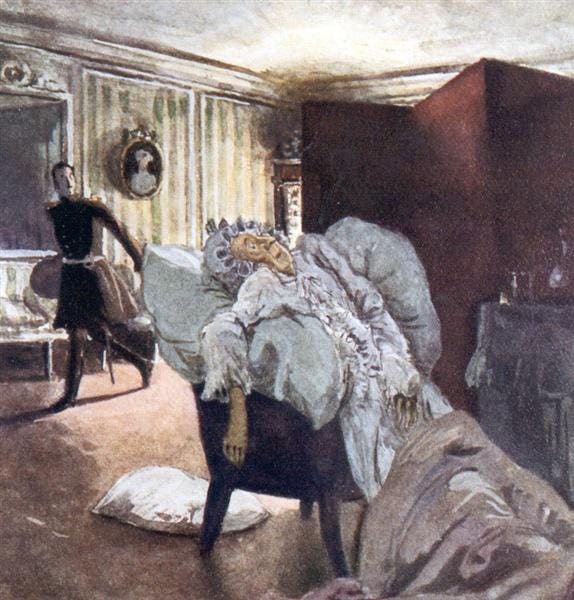

Hermann followed the directions given to him by the poor girl, Lizaveta Ivanovna. But he did not mean to sneak into the girl’s room. Instead, he proceeded to the old countess’s room to scare the lady to death, quite literally. Meanwhile...

Illustration by Alexandre Benois

Лизавета сидела.

Lizaveta was sitting.

Lizaveta (Лизавета) [lee-zah-VYE-ta] used to be an equivalent of the English Elizabeth. Currently, the standard form of this name in Russian is Elizaveta (Елизавета) [ye-lee-zah-VYE-ta]. The modern diminutive form in Russian is Liza (Лиза) [LEE-zah], with another derivative diminutive form being Lizan’ka (Лизанька) [LEE-zahn’-kah], with the stress on the first syllable.

Лизавета Ивановна сидела.

Lizaveta Ivanovna was sitting.

The full formal Russian name is structured as follows: first name, patronymic, last name. The patronymic is derived from the father’s name by adding the suffix -ovna/ -evna/ -ichna/ -inichna (feminine) or -ovich/ -evich/ -ich (masculine). In our case, “Ivanovna” is a patronymic, meaning that Lizaveta’s father’s name was Ivan.

Лизавета Ивановна сидела в комнате.

Lizaveta Ivanovna stayed in the room.

The verb “сидеть” often means “to stay” or “to remain somewhere,” and can imply “to be located.” In this context, the fact that she was seated rather than standing is irrelevant.

Лизавета Ивановна сидела в своей комнате.

Lizaveta Ivanovna stayed in her room.

“Свой” is a Russian possessive pronoun that roughly means “one’s own.”

It refers back to the subject of the sentence, preventing ambiguity. It would be implausible to say “Она сидела в её комнате” meaning “in her room” in Russian.

Лизавета Ивановна сидела в своей комнате, погружённая в размышления.

Lizaveta Ivanovna stayed in her room, deep in thought.

Погружённая, or погружённый в размышления is a common participial phrase in Russian describing someone who is deep in thought or lost in thought and not paying attention to anything around them.

Example:

Молодые люди с папиросками ходили тут же взад и вперед, не обращая никакого внимания на барышень, и казались погружёнными в размышления. - А. Куприн

Young men with cigarettes walked back and forth, paying no attention to the young ladies, and seemed lost in thought. - A. Kuprin

Лизавета Ивановна сидела в своей комнате, погружённая в глубокие размышления.

Lizaveta Ivanovna stayed in her room, deep in thought.

The adjective глубокие (“deep”) adds little to the meaning in English, but it does in Russian.

Лизавета Ивановна сидела в своей комнате, в наряде, погружённая в глубокие размышления.

Lizaveta Ivanovna stayed in her room, dressed up, deep in thought.

“Наряд” in Russian refers to an outfit, usually something stylish, festive, or meant for a special occasion. Lizaveta Ivanovna has just returned from a party in her ballroom dress.

Лизавета Ивановна сидела в своей комнате, в бальном своем наряде, погружённая в глубокие размышления.

Lizaveta Ivanovna stayed in her room, dressed in her ball gown, deep in thought.

Again, we can see the word “свой” functioning where English normally uses “her.”

Voice of Nikolai Marton

Лизавета Ивановна сидела в своей комнате, ещё в бальном своем наряде, погружённая в глубокие размышления.

Lizaveta Ivanovna stayed in her room, still dressed in her ball gown, deep in thought.

“Ещё” is a very flexible Russian word with several common meanings. The exact meaning depends on context.

Please find in my notes the links to the text of the Chapter IV of The Queen of Spades by A. S. Pushkin and to the audio file of Nikolai Marton reading that chapter.

I enjoy how you gradually expand the full translation of a sentence, and your thorough, academic explanations, Andrei.